May 14, 2006

Privacy and the War

The NSA is in the news again with reports that they asked for, and received, the call records, sans personally identifying information, from all major telcos but Qwest. While it appears that the government didn't violate any laws with this effort, since the data was given voluntarily, the companies may be in violation of the Stored Communications Act or the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (or a host of other telecommunications laws going back to 1934). This new program, coming on the heels of the earlier one to eavesdrop on international phone calls, has brought to the forefront the question of what the proper balance is between security and privacy during wartime. I've been on record defending the previous program, which might seem kind of weird for someone who bills themselves as a classical liberal. And to be honest, I'm not too happy in the abstract about either effort, or the whole idea of the State watching everyone that closely. But there are three reasons I've defended them:- Many people rushed to judgment and claimed that it was clearly illegal before the details of the program came out and without knowing what the law and case law said. In neither case was it obvious from initial reporting that a law, or the Constitution, had been violated.

- Many people who attacked the programs were also quick to accuse the Bush administration of not "connecting the dots" on previous attacks.

- It wasn't clear to me that the invasion into our privacy was any worse than what we put up with on a daily basis for a host of other (less important) reasons.

I'm a strong believer in privacy rights. I don't see why Americans are obligated to give the government their bank account details and the holdings therein. Other revenue agencies in other free societies don't require that level of disclosure. But, given that the people of the United States are apparently entirely cool with that, it's hard to see why lists of phone numbers (i.e., your monthly statement) with no identifying information attached to them is of such a vastly different order of magnitude.People were outraged by the Patriot Act, but many of the provisions simply extended to counter-terrorism tools that the DEA was already using in the War on Drugs. And the NSA calling database program pales in comparison to the pervasive invasion caused by the current income tax regime. Every stock I own, every bank account or piece of real property, the salary I earn, the gifts I give or receive, the tuition, the medical expenses I pay. All of this is already sucked up into a vast database to tell the government how much to expropriate from me. Surely this is a much greater violation than a database of phone numbers I've called. And surely there are other less intrusive means that could be used to gather revenue. And that's where the libertarian in me comes out. If we're going to have intrusive, privacy-shredding policies they should be used where there are few or no reasonable alternatives and where the government has a legitimate role to play. So I don't understand the concern, the national coverage, talk of impeachment, in having these programs for national security when as bad or worse exists to continue a failed policy of drug prohibition or an inefficient policy of tax collection and enforced retirement savings. Defense is a proper role of the federal government. Drug prohibition, enforced savings, and income redistribution are not as far as I'm concerned. So, while it would be consistent for me to support the NSA wire taps and not the others, I'll make this pledge: once we get rid of the IRS and the War on Drugs (which is about a thousand times less likely to end than the War on Terror), and their excesses, I'll get more concerned about what we're doing to try to stop another 9/11.

May 13, 2006

Probability and Predictions

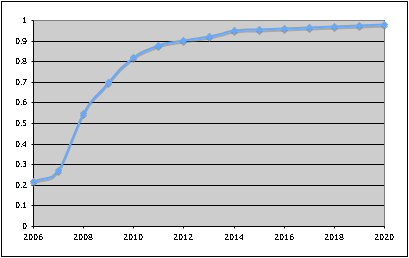

One of the things that has bothered me for some time now is how people make and communicate predictions about the future. To pluck an (important) example from the headlines, the CIA and other intelligence analysts have said that Iran is 5 to 10 years away from being able to build a nuclear bomb. But, even though this number has been quoted hundreds of times, there is never any context to explain what it means. While it's all obviously fuzzy, and in the end of the day someone just looks at all the evidence and puts a number on, it would be nice to be told what is being claimed with those numbers. Is it some kind of confidence interval? "We believe there is a 95% chance that Iran will produce a bomb in more than 5 years but less than 10 years." Is it something else? If we wanted a 99% confidence would it jump to 1 to 30 years, or 4 to 11 years? I'm reminded of the silly little probabilities that Gartner Group pioneered in their industry research ("Microsoft will delay the release of Window 98 until 1999 (0.8 probability)"). I thought those were kind of dumb at the time, but at least you had some sort of indication how sure the analyst was. And you could have, with some work, measured how good of a job she did both in making predictions and in assigning probabilities. But it's still pretty lame as far as imparting information that's useful for making decisions. Even the weatherman hasn't moved past using simple probabilities for chance of rain on a given day. While that may be the best measure for planning a picnic, it's not going to do you much good if you're trying to gauge the chance of a drought (you can't just add up the "chances of rain" each day because they are not independent events). So, what would a good tool for communicating the likelihood of an uncertain future event? Well, returning to the Iranian nuclear program issue, here's what I'd like to see: a distribution showing the cumulative probability of them building a bomb over time. Preferrably, we get to see a pretty little graph, and we'd get one from several sources. Here's an example of what one might look like for the Iranian bomb:

How is this better than what we get in the news? Well, first of all, I can look at it and see that the analysts think there's a one in five chance they already have a bomb. Second, as a policy-maker or voter, I can set my threshold for what cumulative probability I'm willing to tolerate before "drastic measures" need to be taken. Also, I can see which years the slope is highest, which might indicate the timing of any action taken. In addition, analysts could make multiple versions of the graph with different assumptions in place and show us side-by-side what the effect would be. So we could have one graph that showed the distribution if there's a secret military project that's been ongoing since 2003 vs. if the public program is all there is. Now, it's still not perfect. It's intelligence work, and it's only as good as the information, assumptions and analysis that goes into it. And there's no easy way show confidence in the individual assessments that make up the overall distribution (for instance, the assessment that there's a 20% chance that they already have a bomb makes a big difference in the graph, at least in terms of absolute magnitudes – how good was the information that informed that decision vs. the rest?) But, to me, it's much better than "they are five to ten years away from a bomb". Anyway, comments from the mathematical and policy oriented?

April 12, 2006

March 27, 2006

Survival of the Fittest

The debate about evolution has raged in the comments below for several days. And it keeps returning to "survival of the fittest" and whether the concept is a tautology or not. And if not, whether it can produce falsifiable predictions. And finally, whether the answer to this has any bearing on whether evolution is a "scientific" theory. I'll try to address at least the first two below.... Continue reading "Survival of the Fittest"Apropos "absurdity"

In The New Yorker, H. Allen Orr reviews Daniell Dennett's new book, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. The book, an attempt to look at the phenomenon of religion from a scientific view, resonates with my absurd belief below. (Which is, of course, not surprising since I referenced Dennett myself in my post.) But it's funny how similar it sounds:According to Dennett, the earliest stages of religion were likely characterized by speculations about supernatural or quasi-natural beings. These questions arose out of an aspect of human nature we take for granted: the recognition that the world contains not only other bodies but also other minds. We recognize, in other words, that the world includes "agents" independent minds that possess their own sets of beliefs and desires. This recognition allows us a wide range of cognitive moves and countermoves presumably unavailable to most other species: "I know he thinks that I have a stone in my hand." The ability to attribute agency is, Dennett says, almost surely an evolutionary adaptation. It is probably encoded genetically in our species (no one taught you that other minds populate the planet), and it plays a key role in everything from fighting ("He doesn't know that I dropped the stone") to seduction ("Would you like to see my cave paintings"). But its appearance during evolution led to an unexpected possibility: attributing agency where no agent exists. Human beings are skilled at positing agents — whispering winds, turnip ghosts, and monsters under the bed — for which the evidence is less than overwhelming, and this tendency might explain why nearly all peoples talk about creatures like elves and goblins. (Emphasis added)Anyway, it just struck me, coming so closely on the heels of the other post.

March 25, 2006

More France

An unusually blunt and bleak piece about France's latest woes at the Washington Post:This is the second time in four months that France has been seized with violent protests. And in an important sense, these are counter-riots, since the goals of the privileged students conflict with those of the suburban rioters who took to the streets last November. The message of the suburban rioters: Things must change. The message of the students: Things must stay the same. In other words: Screw the immigrants.I feel a bit foolish for thinking this, but I can't help but think that there's a real chance that France's civil unrest might, in the not-so-distant future, turn into an actual civil war. This could, perhaps, qualify as another absurd belief.... But the mix of ingredients in French society is unquestionably volatile:

- An elite clinging to outmoded social structures, failed policies, a rigid language, and past glories.

- A national proclivity towards revolutionary convulsions (how many Republics per century is optimal?)

- A political class trained to manipulate the mob

- A persitent underclass of unassimilated immigrants who, rightly, feel excluded from the social protections of the state

- A strong, organized network of radicals who swim within the unassimilated sea, preach extreme religion, and receive support from foreign governments

- A brewing generational conflict between the older (more native) French who benefit from the social policies and the younger (more immigrant) French who will be asked to bear the cost, with no hope of reaping the same pay out

- Spoiled students who believe their "resistance" links them to the revolutionaries of '68 when their insistence on the status quo and sense of entitlement makes aristocratic reactionaries a better analogy.

Israel Lobby

While it hasn't gotten a great deal of press, the recent "working paper" from the Kennedy School on the The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy has sparked a lot of outrage. It's truly remarkable what these two professors wrote and considered "scholarship". It's the kind of stuff that makes conservatives think that the Academy is irredeemably screwed up. Alan Dershowitz is not happy about it at all, as you'd expect, and claims to have traced certain out-of-context quotes back to anti-Semitic and neo-Nazi hate sites. Frankly, my biggest problem with the paper, which I finally got around to reading some of, is how bad it is. Just really, really shoddy work. I can't believe anyone would call this scholarship and think they could get away with it:U.S. foreign policy shapes events in every corner of the globe. Nowhere is this truer than in the Middle East, a region of recurring instability and enormous strategic importance. Most recently, the Bush Administration’s attempt to transform the region into a community of democracies has helped produce a resilient insurgency in Iraq, a sharp rise in world oil prices, and terrorist bombings in Madrid, London, and Amman. With so much at stake for so many, all countries need to understand the forces that drive U.S. Middle East policy.Gosh, that starts off well-balanced. At this point, they've convinced me that they really are seeking the truth and not just spouting propaganda.

Instead, the overall thrust of U.S. policy in the region is due almost entirely to U.S. domestic politics, and especially to the activities of the "Israel Lobby." Other special interest groups have managed to skew U.S. foreign policy in directions they favored, but no lobby has managed to divert U.S. foreign policy as far from what the American national interest would otherwise suggest, while simultaneously convincing Americans that U.S. and Israeli interests are essentially identical.1Really? I thought it was Halliburton and the House of Saud that drove our policies. Go figure. Gotta love that first footnote:

1Indeed, the mere existence of the Lobby suggests that unconditional support for Israel is not in the American national interest. If it was, one would not need an organized special interest group to bring it about. But because Israel is a strategic and moral liability, it takes relentless political pressure to keep U.S. support intact.What kind of logic is that? Are you telling me that this is the kind of model of public action that qualifies as political science these days? I didn't realize that current scholarship started from the premise that there is some uncontested "real" American national interest? But there must be, because the "mere existence" of the Isreal lobby proves it's at odds with pro-Israeli positions. Do you like the rhetorical slight-of-hand that introduces, at the last minute, the straw man of "unconditional support" that is supposedly given to Israel? And if we're starting (in footnote 1!) with the fact that Israel is a strategic and moral liability, then why do we need the paper at all? They then make a one-sided case that Israel is a strategic liability – but if I toted up the costs of any one of our alliances, while ignoring the benefits, I'm pretty sure I could end up with a negative balance too. As Dan Drezner points out, they completely skipped over incidents (like the Iraqi nuclear program at Osirak or intelligence sharing) where the alliance was an asset. Anyway, I could beat my head against the wall, trying to debunk each assertion in the paper, but it's not worth it. It's clear from the first three pages that it's an ideologically driven hatchet job and not scholarship. I really hope serious political scientists (and Harvard and Chicago) distance themselves from this kind of work product fairly quickly.

La petit vessie de Chirac

I thought that I would allow myself to quietly gloat about this, but at the advice of a friend, I will laugh my ass off:PRESIDENT CHIRAC stormed out of the first session of a European Union summit dominated by a row over French nationalism because a fellow Frenchman insisted on speaking English.... When M Seillière, who is an English-educated steel baron, started a presentation to all 25 EU leaders, President Chirac interrupted to ask why he was speaking in English. M Seillière explained: "I'm going to speak in English because that is the language of business." Without saying another word, President Chirac, who lived in the US as a student and speaks fluent English, walked out, followed by his Foreign, Finance and Europe ministers, leaving the 24 other European leaders stunned. They returned only after M Seilière had finished speaking.And I would have to agree that this is the best part:

Embarrassed French diplomats tried to explain away the walk-out, saying that their ministers all needed a toilet break at the same time.Vive l'impérialisme culturel Anglo-Saxon!

March 24, 2006

Vendetta

Julia and I just got back from V for Vendetta and I really enjoyed the movie. It did a very good job of building tension, making the oppression palpable, and making you feel invested in the characters. The dialogue, which began with the unbearable pretension of V's alliterative and eponymous soliloquy, eventually found its stride and "worked" with the story. This despite the Wachowskian tendencies towards verbosity familiar to fans of the Matrix. The relationship between Evey and V was complex and satisfying, the back story horrific, the torment credible. The movie pays unabashed homage to Orwell and owes much more to Nineteen Eighty-Four than just John Hurt – though it is gratifying in some twisted way to see an aged Winston recapitulate Big Brother's close-up talking head. Still, it manages to allude to the previous depictions of totalitarian governments without being exactly the same. It achieves this partially by examining the moral ambiguity behind the fact that "one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter". While often questionably applied (the takfiri "resistance" in Iraq are in no way comparable to Minutemen), there is a relativistic point worth making here. In short, the movie was a decent parable of the dangers of totalitarianism and demagoguery in the modern age, layered on top of an exploration of acceptable forms of resistance. Unfortunately, rather than be content with the eternal relevance of that theme, it ended up a weaker movie than it could have been by trying to be especially relevant for today. This was my fear going into the movie, and it was born out to some extent. More, including maybe spoilers, below the fold... Continue reading "Vendetta"March 22, 2006

"Absurd" belief

It seems the blogosphere is awash in "absurd" beliefs. Not one to miss a bandwagon, I'll confess one (of probably many) of mine. It's actual a "contentious" belief combined with an "absurd" just-so story of sorts:The Self is nothing more than a story we tell ourselves about our beliefs, desires, and actions. Moreover, this story-telling is tied in to the way we store memories, make plans, and interact with others. This narrative capability co-evolved as a Self-describing and Other-describing capability in proto-human societies.Rather than leave the belief to wallow in it's own absurdity, I feel compelled to tell the just-so story of how I think this happened. As Daniel Dennett describes, the Intentional Stance is an approach to modeling the world where cause and effect are under-girded by beliefs, desires, and intentions. It, like the physical and design strategies, has utility in describing (and predicting) the behavior of many types of agents (humans, animals, even mechanistic controllers like thermostats) in certain circumstances. My belief (or so I tell myself) is that humans developed a proto-ability to tell these kinds of intentionality stories, most likely about predators and prey (it's thirsty so will go to water, it's hungry so will try to eat me), to help plan and reason about daily situations common to hunter-gatherers. And then something happened. This ability turned out to be just as useful in describing and predicting the behavior of the other members of the tribe. And it turned out to be pretty good at modeling their own behavior too. And then a virtuous cycle was set up: the more individuals acted as if they had beliefs, desires, and intentions the better the other members of their tribe could predict their behavior and effectively cooperate. (Or, for you cynics, better dissemble and free-load off of the others). So a race between tribes began as to who could most thoroughly internalize the new model.... and eventually the Self was born. Humans became expert at attributing beliefs and divining intentions. Belief and desire drove decision and action, and decision and action gave witness to belief and desire. And eventually humans actually did believe and intend, because they acted indistinguishably from agents with beliefs and intentions. And through these attributions and divinations, these decisions and actions, humans created values and most importantly become the architects of their own identities. In the end, the advantage conveyed by adopting this stance became so overwhelming, both to the individual and the group, that incredibly complicated – even outrageous – mechanisms evolved to maintain the illusion and consistency of the Self. Our story-telling capability was upgraded to allow us to tell ourselves whoppers that kept the narrative flow going and made our (and others') beliefs and desires appear consistent. And that's how Man gained his Self and became the Architect of his Identity. Pretty absurd, eh?

March 11, 2006

Why Appliances Buck the Trend (or Economic Illiteracy)

So I was all ready to point to this article at the New York Times as an interesting and timely follow-on to my post below on incomparability.... but instead, I'm forced to write about economic illiteracy in the media. The article starts off well discussing how "white good" prices have gone up while consumer electronic prices have gone down dramatically. The reason? The growth in sales of the high-end stylish models (aesthetic improvements) and the increased energy efficiency requirements mandated by the federal government. So it jibed pretty well with my post. Then comes this unbelievable piece of journalism:Let's say you are enamored with Whirlpool's Duet, the country's top-selling front-loaded washing machine. It is one of the more energy-efficient machines using about 227 kilowatt hours of electricity a year, according to a government rating that appears on the yellow Energy Guide sticker affixed to all new appliances. You can find one at Sears or other appliance stores for about $1,400. (Of course, the cost won't end there. Unless you buy a matching Duet dryer at about $900 to sit next to it, your laundry room will look like a squinty-eyed pirate.) The Duet washer would cost about $78 a year to operate compared with $161 a year for Whirlpool's $549 Ultimate Care top-loader, according to a downloadable calculator on the Department of Energy Web site (http://www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?fuseaction=find_a_product). But because the Duet costs so much to buy, the total cost of the front loader over seven years is $1,946, or $269 more than the Whirlpool classic top loader. Guess what? It makes economic sense to buy the more expensive machine. In theory, a dollar today is more valuable than a dollar in seven years. Therefore, you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years. (You can do this "present value" calculation at http://www.csgnetwork.com/presvalcalc.html). That calculation will be useful anytime you buy a product that promises future savings.Can you spot the howler? Because the upfront cost of Duet comes first, it should have to save you that much more than the cheaper model over the seven years. In other words, because a dollar is "in theory" worth more today, the Net Present Value (NPV) calculation works against the expensive model... but they've presented it as working in its favor. Two seconds of thinking about this showed me it couldn't be right. How could this end up in the "Your Money" section of the New York Times and not be caught? Update: I've been thinking about this a bit more and I just can't figure out what happened to get these paragraphs published in the NYT. Perhaps some radical last minute editing that accidently got rid of other sentences that would have explained it? I doubt it, but what in the world does the fact that "you should be willing to pay $318 more for something that saves you $546 over seven years" have to do with anything in the article? From the math I do, the Duet washer saves you $581 in energy costs over the seven years, but costs $851 more to buy. Where do the $546 and $318 come from? The closer I look the more this just seems like innumeracy on top of economic illiteracy.

March 08, 2006

On Incomparability

One of the things I've been thinking about recently is the difficulty in comparing and/or equating different products so that you can derive meaningful metrics about the category. To some extent this is a reflection of a larger ontological problem of deciding which objects are meaningfully the same, but it has special relevance in an economic world defined by technological progress. While this may seem somewhat esoteric, I would argue that it's incredibly important to understand this phenomenon because it systematically makes us overestimate inflation, underestimate standard of living increases, and, in general, be more pessimistic than warranted about Progress (with a capital 'P'). This difficulty is particularly problematic when trying to measure the price of something over time or space. As a simple, mundane example, take the price of gas over time. While we pretend that there is some consistent thing called "gasoline" and that it's price is denominated in something consistent called US dollars, there are three things that make it difficult to compare the prices over time:- The distinction between nominal dollars and real dollars. This is the most obvious, and most serious people writing about prices over time will use some kind of constant dollars. The leading ways of doing this (chained or unchained CPI, GDP deflator, etc.) are all valiant attempts to address the Incomparability Problem, but all have serious flaws (that I'll discuss more below). But under any scenario, a dollar 50 years ago is not worth the same as a dollar today.

- The gas itself has changed. While gas seems like a nice, simple commodity, handily measured in concrete units like gallons, the term hides the fact that gas has changed dramatically over time. Tetra-ethyl lead content, octane level, ethanol and MBTE admixture, volatility – all these make the gas you buy today very different from 30 years ago. For instance, maximum allowed volatility is lower today in order to reduce emissions during refueling (resulting in a "better" product for some definition of better.) How does/should this impact your analysis of price change over time?

- Consumers don't really care about gallons of gas, they buy "passenger miles", or maybe even "cargo miles". As with many products, the utility that consumers get out of the product is coupled to a complex network of enabling technology that itself changes over time. The fuel efficiency of engines has gone up dramatically over the last several decades allowing cars to go further (or haul more) for the same gallon of gas. If my car today can go 29.1 miles per gallon vs. 18.8 MPG in 1977, how does/should that factor into the "real" price of gas?

- Medical care – rather than across time, medical care illustrates the problem across regulatory regimes. Is cancer treatment, for instance, the "same" when you have to wait months for treatment vs. a couple of weeks? While the treatment itself may be the same, factors around the provision of the treatment make the former a qualitatively different product than the latter, particular if it means the difference between success or failure. If we pretend they are the "same" we will be confused why people pay more for the latter (in the US) than the former (in Canada).

- Frozen food – one effect of recently having a baby has been a sizable uptick in the amount of frozen food that Julia and I eat. I have to say that I have been truly astounded at the quality of the frozen food available at the grocery store – specifically the change in quality from when I was a child and last ate my share of "TV dinners". Now, these new frozen foods probably cost more (even adjusting for inflation) than the old ones, but how does one compare the price of excellent frozen Indian dishes, vegetarian Mexican food, health food, etc. with the Hungry Man™ and other meager selection we had in the early eighties? The situation is replicated in every category of food. How many more options does the butcher store at the supermarket now offer? Do you even remember when fruits and vegetables had seasons, out of which you were out of luck? If we pay twice as much for avocados, but we can get good ones in February, how do we count that?

- Housing – while often lamented as a component of sprawl, it's uncontroversial that the average American home has gotten significantly larger over the last several decades. Meanwhile, housing costs as a share of family income have stayed relatively flat or decreased (driven primarily by lower nominal mortgage interest rates and higher family income), even with the current bubble. Can we call wages stagnant if the same percentage of them buys more house each year?

- Consumer electronics – the fast-paced world of high-tech gadgets is obviously problematic. An ever larger portion of consumers' income goes to computers, MP3 players, digital cameras, televisions, cell phones, etc. By any measure of delivered features (gigahertz, megapixels, gigabytes, diagonal viewing area, etc.) there has been massive deflation in these product areas. Five years ago, the iPod didn't exist. Now, more than 41 million of them have been sold, with 14 million in the first quarter of 2006 alone! Sure, I paid a heck of a lot more for "mobile music device" (four times as much?) than when I bought my first WalkMan®, but is that really relevant?

March 06, 2006

Robotic Pack Mule

The New Scientist reports :A nimble, four-legged robot is so surefooted it can recover its balance even after being given a hefty kick. The machine, which moves like a cross between a goat and a pantomime horse, is being developed as a robotic pack mule for the US military.Check out the video here. Now, I actually think this is extremely cool and far be it from me to question new gadgets, but.... if the military really needs 'pack mules' then why don't they, um, you know, use mules? Like real ones. The current model of the robot can carry 40 Kg and can cross somewhat rough terrain. While it's just a R&D prototype, it's not stacking up too well against the flesh & blood type so far.

February 23, 2006

Port Deal

The latest political showdown and Bush Administration controversy seems to be the UAE ports deal. Everyone seems a bit shocked that Bush has threatened to veto any legislation blocking or delaying the deal, and that he did it so quickly and forcefully. Bipartisan condemnation of the deal is on the rise and a veto-overriding super majority may be in the making. So the question is, why is Bush doing this? There are four possibilities that come to mind:- Bush has lost whatever marbles he had and he and Cheney are colluding with their cronies and Arab oil buddies to the detriment of US security. This seems to be the standard argument of the crowd that claims that the Iraq War was all about Halliburton profits.

- Bush is simply reacting to Congress' attempt at oversight in a predictable (for him) way. He maintains his right to act unilaterally on matters of foreign affairs and is not about to let Congress tell him what to do. Whether you think this is an example of Bush trying to slip something by Congress and being unreasonable in response to their attempts at oversight, or of opportunistic Congressmen making a last-minute stink for political advantage over a properly vetted executive decision, seems to depend somewhat on your partisanship.

- Bush has made the port deal part of a larger diplomatic deal with the UAE and is fighting hard not to have it scuttled. Despite their often anti-Israeli stance and persistence as a money-laundering hub, they are one of our (useful) allies in the Middle East, and this deal may be a quid pro quo either retrospectively for help during the Iraq War, or in exchange for future help (for instance, in any coming confrontation with Iran). Bush is willing to use his veto, and expend political capital, to keep that deal going forward.

- Bush made the port deal part of a larger deal with the UAE, but wants Congress to get him out of it. This may seem unlikely, but Presidents often play the good guy to smooth foreign relations, while relying on Congress to do the necessary dirty work. Clinton and the Kyoto Protocol come to mind as a somewhat recent example. In this scenario, the UAE would have made much-needed support in current or future operations contingent on the port deal. The Administration, recognizing the need to keep them as an ally, but also the foolhardiness of giving them port operations, decides to publicly support the deal while maneuvering to get it killed by Congress. The more political capital he expends (and the more forcefully he expends it) the more likely the Emirates are to believe that he did the best he could. We may then be able to maneuver them to a more acceptable pay-off for support.

February 20, 2006

Fixing Copyright

I've posted several times about copyright law and other intellectual property issues, and I've discussed my concerns about the stagnating public domain here. Rather than just complain about things, I'd like to spend a bit more time on this blog posting some policy proposals to make things better. So here's my proposal for how to fix the copyright system. Continue reading "Fixing Copyright"February 18, 2006

On Warranties and Demography

In my day job, we work with companies (manufacturers and retailers) on optimizing their extended warranty businesses. Recently, I was struck by how a common problem that these businesses face is analogous to a more general problem that Western nations face. In a nutshell, it's the problem of switching from a Growth Mode to a Stable/Declining Mode. Continue reading "On Warranties and Demography"February 15, 2006

Europe Doomed?

Theodore Dalrymple has an essay up at Cato Unbound questioning whether Old Europe is doomed. It brings up the usual suspects of over-regulation, demographics, unassimilated immigration, and protectionism. There are some interesting followups from Timothy Smith, Charles Kupchan, Anne Applebaum. I have to say, though, that if this is the response to cartoon riots for much longer, they may very well be doomed:“We had to watch how they were ripping off car mirrors. We wanted to stop this vandalism but were ordered to withdraw,” an anonymous policeman says in today’s Flemish daily De Standaard. “An ambulance was told to switch off its siren because that might provoke the Moroccans.” Another anonymous officer told the press: “There you are watching this, while citizens can see that you are powerless.” According to an anonymous police chief the authorities decided, that “it was better to have a few cars vandalized than risk open war in the streets.” On Monday the city council, led by the Socialist mayor Patrick Janssens, decided that the city would compensate the damage to cars and property.The thing that the authorities don't seem to understand is that, rather than defusing the situation, they are pouring gasoline on the flames. These actions will be seen as nothing more than additional examples of Western weakness and decadence. The capitulation will engender nothing but scorn and loathing from the radical Islamists and unassimilated immigrants. It seems to me that they are falling further into the wishful-thinking trap of "if we just don't provoke them...."

February 06, 2006

Misguided Policy

Via Knowledge Problem, I saw this post by Marcus Cole at blackprof.comThe State of Illinois enacted a law that requires all mortgage applications within nine Chicago zip codes to undergo a process of review by the state’s Department of Financial and Professional Regulation. The department’s review process determines whether mortgage applicants in these neighborhoods must undergo compulsory credit counseling. If they must, then the mortgage lender must pay the cost of the counseling.He notes that these nine zip codes are predominantly African-American neighborhoods and that, while most likely good-intentioned, this legislation will significantly increase the cost of mortgages to people living in those areas and will subsequently decrease the price they can pay for houses, depressing prices. This law is a perfect example of misguided policy that is completely divorced from reality. Let us assume for a moment that the backers of this law actually do have good intentions and are worried about predatory lending (and are not people or companies hoping to capture rents from the new law – credit counseling agencies, for instance). It is still a really bad idea. The first common, and most obvious, mistake is not understanding the incidence of the costs associated with the law, i.e. who will end up paying for the counseling services. While the statute asserts that they must be born by the lender, it's foolish to assume that who pays the check actually bears the cost. The mortgage market seems to be a fairly competitive market, meaning that the price of mortgages will be close to the marginal cost. Thus, anything that increases the marginal cost (like mandatory credit counseling) will be passed on as higher prices (i.e. higher interest rates, points, or fees). Wishing for the banks to pay will not make it so. The second, and arguably more pernicious, problem is that the law denies, or at least ignores, the agency of the people it is purportedly trying to help. On one hand, it offers them no choice in the matter, making the counseling obligatory, and on the other, it ignores the choices that will likely ensue. (I say pernicious because I believe that the more policies we institute that minimize the agency of the citizenry, the more likely we are to end up with a populace that is dependent on government action and incapable of effecting change. As Marcus states, laws like these are often "motivated by an unspoken belief that poor black people are incapable of making important decisions for themselves." The continuation of this belief serves neither the poor black people nor the rest of the country. I, in fact, would expand his formulation to say that laws are often motivated by the unspoken belief that people, or any race or income level, are incapable of making important decision for themselves – and I fear the day when they aren't because of it.) A moment's thought, with a mental model that assumes that at least some of the people affected will be rational actors, shows that this law is likely to be, if not a death sentence, then a slow withering plague on the neighborhoods. As mentioned above, housing prices will go down virtually overnight in those neighborhoods as the demand curve shifts down (due to higher mortgage rates). Existing owners' equity will evaporate, decreasing the likelihood and affordability of needed improvements. Over time the neighborhoods will decay relative to nearby ones. Beyond that, the marginal home buyer, seeing that her money can get more house outside the nine zip codes than within, will choose to leave the neighborhood. Not only will this entail the flight of capital, as buyers take their saved down payments with them, but also the flight of human and social capital – the responsible neighbors capable of saving that down payment. Now, of course, not everyone can or will leave, but on the margins the effect could be enough to further drain housing prices – leading to a vicious circle and eventual blight. Presumably this is not the desired effect. Unfortunately, policies like this are a dime a dozen in this country. They sound good on the surface, they have a noble cause that lobbyists can latch on to, but they are built on bankrupt, and depressing, models of human behavior that thankfully are not yet reality.

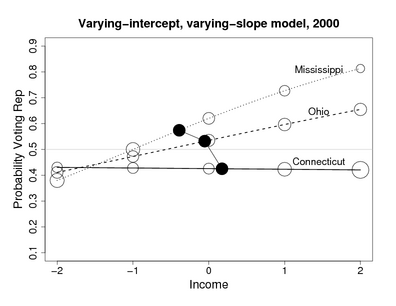

Red, Blue, Rich, Poor

Kevin Drum notes an interesting paper (PDF) on Republican voting in poor states vs. in rich states. The author of the paper has a blog where he discusses the results. The argument is that in rich states (like Connecticut, the richest) poor voters vote Republican in almost the same amount as rich voters do (i.e. the slope of percentage voting Republican as a function of income is pretty flat). On the other hand, poor states (like Mississippi, the poorest) poor voters vote Republican much less than rich voters do (i.e. the slope is fairly positive). In fact, they show that this result works across states with the slopes being negatively correlated with state-wide income. Here's the finding in a pretty clear (once you ponder it for a sec) graph: I actually think the graph is excellent – it packs a lot of information into a small space. The y axis is the percentage voting Republican in the 2000 election, the x axis is a quantile-based scale of individual income, the open circles denote the number of voters in each quantile for each state and the black circles show the mean income for the state.

So I'm with them so far, but then I thought... wait a second, what exactly is the "quantile-based scale" for income? A first glance, it's likely that it's a national scale because there explicitly are different quanitities shown in each quantile for each state – that wouldn't make a lot of sense if they were state-specific quantiles. Looking at the paper, I see this footnote on page 6:

I actually think the graph is excellent – it packs a lot of information into a small space. The y axis is the percentage voting Republican in the 2000 election, the x axis is a quantile-based scale of individual income, the open circles denote the number of voters in each quantile for each state and the black circles show the mean income for the state.

So I'm with them so far, but then I thought... wait a second, what exactly is the "quantile-based scale" for income? A first glance, it's likely that it's a national scale because there explicitly are different quanitities shown in each quantile for each state – that wouldn't make a lot of sense if they were state-specific quantiles. Looking at the paper, I see this footnote on page 6:

The National Election Study uses 1 = 0–16 percentile, 2 = 17–33 percentile, 3 = 34–67 percentile, 4 = 68–95 percentile, 5 = 96–100 percentile. We label these as −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, centering at zero so that we can more easily interpret the intercept terms of regressions that include income as a predictor.The assumption has to be that those are national income percentiles. And it's worth noting that they are most definitely not quintiles – they are very uneven. The paper's 0 and 1 include 61% of the electorate while 2 only includes the top 5%. Why these specific breaks are used is not stated, but it would be interesting to see how the results would change if different breaks where used. It also makes it difficult to visually interpret the size of the circles on the graph. But back to my main point: these are national quantiles. The problem with this is that I would posit that any "income-effect" on political persuasion would have a lot more to do with relative income within your peer group, and to the extent that it is absolute, would be modulated by cost-of-living adjustments. Looking at the chart again, and knowing that it's the poorest state, it seems clear that the people in income level 2 in Mississippi must be much less than 5% of the state electorate, while those in income level 2 in Connecticut must be more than 5%. For the sake of argument, let's say that income level 2 in Mississippi is 2% of the electorate, while in Connecticut it's 8%. I would expect the top 2% of a state's electorate to be pretty different from the top 8%, even if the absolute ranges were the same, simply because their relative "status" on the income scale is significantly higher. And that's before we take into consideration that after cost-of-living adjustment, the 2% of Mississippians in that top national ventile would feel much more rich than the 8% of Connecticutters in it. Likewise the bottom quantile must be much bigger than 16% in Mississippi and much smaller than 16% in Connecticut. Similar relative income and COLA effects would occur as on the top side. So here's an alternative hypothesis for the results they're getting: in each income quantile the Mississippians feel richer than the Connecticutters in the same quantile and therefore they vote Republican. This can be seen as a slight twist on the economic determinism argument, with subjective, relative income replacing objective, absolute income as the determinant. So would correcting for this make the effect they found go away? Probably not... or at least it's not clear that it would. But it would be interesting to see how the model held up on state-specific quantiles and/or COL adjusted ones. Would the top 2% of Connecticutters be more Republican than the top 8%, thus pushing the slope positive and diminishing the overall effect? I look to my statistical friends to catch any errors I've made in my logic.

February 04, 2006

Boston Globe on the Cartoons

I'm sorry but this editorial is pathetic. It conflates all sorts of stuff in an absurd melange of platitudes that shouldn't pass for rational thought, much less publishable opinion. First, it is debatable whether the initial publishing of the cartoons was a good idea. It was obvious that they would be offensive to Muslims, and restraint probably would have been wiser. But it's completely disingenuous to act like the freedom they were exercising was not under attack. Perhaps the Danish government had not outlawed depictions of Mohammed, but the EU has debated laws restricting "racist" or "religiously intolerant" speech. And there is definitely an active movement to increase the restrictions. Plus, you have to regard the fatwas against Rushdie and the murder of Theo van Gogh as attacks on that freedom. Yes, perhaps "no government, political party, or corporate interest" was trying to stop them, but a violent and extreme segment of society was. The freedom of speech and the press definitely is under attack in Europe. Perhaps the parochialism of the Globe's editors makes that hard to see. Second, even if the freedom wasn't under attack when the Jyllands-Posten published the cartoons, it definitely was when the other European papers spasmed in "a reflex of solidarity". While the editorial elides this fact and puts the other papers in the same category as the first (a category that they righteously eschew), it's worth remembering that when the other papers followedd, threats, from bombings to boycotts, had been leveled against the original publisher and Denmark. The freedom of the press surely was under attack by then. In addition, by this point it was an important news story in its own right, and the public should be able to judge for themselves the offensiveness of the cartoons. Third, the moral equivalence of all types of "offense" is atrocious. Nazi caricatures of Jews are particularly bad because they are representational of a desire (and historical attempt) to exterminate the Jews. Likewise, with the Klan. That's why a burning cross isn't constitutionally protected -- because it is associated with an implied threat of violence and intimidation. The cartoon of Mohammed, even if intended to offend, even if disrespectful, is not the same as the others. There is no identification with a desire to wipe out or subjugate all Muslims. For the same reason, eating a pork sandwich or letting women drive, while "offensive" to some Muslims, is not on the same level as the Nazis. There are at least three levels that are worth considering: (1) offensive with no intent to offend, (2) offensive with intent to offend, and (3) offensive with an implied threat of violence and/or subjugation. Wearing a bikini, publishing the cartoons, and Nazi hate cartoons most likely fall into levels 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Fourth, the idea that the root cause of this controversy is the "refusal of each camp to recognize and respect the otherness of the other" is absurd. The otherness (radical Islam) of the other (fundamentalist Muslims) requires them to reject the otherness (freedom of speech, tolerance) of us (broadly, the West). The idea that respecting otherness can somehow solve everything is at the core of multiculturalism – and it's pure nonsense. Sometimes othernesses are at odds with each other and we, in our capacity as moral agents, have to judge which is good/right/just and which is evil/wrong/unjust. The proper lessons of multiculturalism are that (1) not all, or even many, differences must be judged or reconciled and (2) we should try to judge without prejudice, chauvinism, or an ethnocentric bias – we should be open to us being wrong and the other being right. In this case, I have no qualms contending that our otherness is hands down morally better than the other's otherness. Fifth, the "ultimate Enlightenment value" requires us to be tolerant even of intolerance – so long as it's non-violent. The one thing we must be intolerant of is violent intolerance itself. Thus, while tolerance says we can critique but must accept the Danish cartoons, and can critique but must accept the Boston Globe's editorial, can even critique but must accept this blog post, it says we must reject the violent reaction of extremists. Why in this editorial is their no mention of the unacceptable threats of violence in response? Was there no room after pointing out the other newspapers' sins to condemn the response? The closest we get to condemning the reaction is a remark that Muslim countries's demands "show[] a misunderstanding of free societies". Finally, the paper's hypocrisy is palpable. Christians can be offended without concern, but Jews, Muslims, and blacks can't. Some fundamentalist Christians are extremely offended by homosexuality and the idea of gay marriage – should we avoid offense by calling those subjects off limits? Government funding of offensive art is fine, but private publishing of cartoons is intolerant. Where was the outrage when this picture of Ariel Sharon eating a Palestinian baby was published in England? Or the brown sugar or other racist ones about Condoleeza Rice? False stories of Quran flushings should be repeated (despite the harm to national security, the incitement to violence, and disrespect to Islam associated with such reports) because they are important news. I don't think Christians deserve any more protection (i.e. very little) than the other groups and I think true stories of Quran desecration are important news, but fitting the editors' past, or imputed, stances with this op-ed is difficult.January 14, 2006

Lithwick on Alito

My friend, Brad, points me to the latest from Dahlia Lithwick about the Alito hearings, with the following admoniton:I know you described this writer as a "screecher" last time around, but I think she's pretty on point here.While this latest certainly qualifies as a more clever exposition than the previous column he pointed me to (which, for the record, I believe I labelled "hysterical" rather than characterizing the author, herself, as a "screecher"), I think her entire mildly sarcastic argument stumbles on this point:

Federalists espouse a view of the Constitution and the allocation of government powers that largely differs from yours; it may indeed differ from that of most Americans.That, I believe, is the root of the problem. Liberals don't want to believe that these Federalist creatures have views that are actually in the mainstream. They try to pretend that spousal notification of abortion (with significant outs for risk of abuse, etc.) are beyond the pale because they threaten the gospel of Roe v. Wade — while 70% of the American populace supports them. Many of the positions that they try to portray as "out of the mainstream" are, for better or for worse, very much in the mainstream right now. If Dahlia Lithwick got out of the back offices of Slate (and perhaps Washington, DC as well) she'd realize that the Federalist, domesticated or wild, is not such an unusual creature. Finally, her return to the tired (and bogus) talking point about the strip search of a 10-year old proves where she's coming from (the left) and what she's interested in (the polemic). So while it's more interesting in style and more readable than her earlier work, it's ultimately.... kind of lame.

January 13, 2006

FISA and the NSA

The NSA surveillance story has been in the news for a while now, and there has been a great deal of commentary in op-eds and on law blogs about whether the actions taken were legal or not. There are actually two questions about the program's legality: was it unconsitutional (i.e. did it violate the Fourth Amendment) and did it violate statute — specifically the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). (There are secondary questions about Article II powers and the Authorization to Use Military Force passed after September 11th, but those questions aren't reached unless one of the first two is answered in the affirmative). Now, wanting to understand the issue, I actually read the law and it turns out that a great deal hinges on the definition of "electronic surveillance" in 50 USC 1801(f). Suffice it to say that it's not a simple definition. In fact, it's been likened to Swiss cheese – the idea being that after the Nixon fiasco Congress wanted to be seen as doing something but also wanted to leave enough holes for national security to be protected. Since understanding the definition of "electronic surveillance" is so central to determining whether the NSA program violated FISA, I decided to parse the definition: As you can see, there are lots of scenarios (assuming I've read the law correctly) where FISA does not apply. While I'm not sure we currently know enough about the actually workings of the NSA program to know where it falls out in the chart, as more becomes apparent, hopefully this will be useful.

As you can see, there are lots of scenarios (assuming I've read the law correctly) where FISA does not apply. While I'm not sure we currently know enough about the actually workings of the NSA program to know where it falls out in the chart, as more becomes apparent, hopefully this will be useful.

January 02, 2006

Artwork

In case anyone was wondering, the faces at the top of the page are pencil drawings that I did about 12 years ago on a trip to Europe. I scanned them and converted them into icons. Both, if I recall correctly, are copies of sketches by Leonardo da Vinci — the latter a self portrait, I believe.

All in all, I was pretty happy with how good these full-sized drawings looked after that much manipulation.

The Name

So, I've relaunched the blog with a new name. I've gotten rid of the somewhat silly Just-in-casionally and the very silly Not-so-oftenally, as well. And I've replaced it with what I hope will be a more permanent name: Quicksilver Sulfide. Why this name? Let's just say that this particular chemical compound, mercuric sulfide, has particular resonance with me. But beyond the eponymous reasons, I also like the fact that it combines two alchemical elements: Quicksilver, or Mercury; and Brimstone, or Sulfur. Quicksilver was believed to transcend both solid and liquid states and is one of the seven metals of alchemy. It also represents Hermes (or Mercury) — the messenger of the gods — and is called Hydrargyrum ("silver water") leading to it's modern abbreviation: Hg. Sulfur is one of three heavenly alchemical elements, but is also associated with Athena (and, in that weird way of Greek mythology, with Hecate and Demeter too via their shared name, Brimo). And so, eventually, it is linked with Hades or Hell. Alchemist believed that if they could "marry Hermes and Athena" — or, in other words, combine Mercury and Sulfur in the right way — that they could create gold. But no one succeeded. And now, we know better. We know that all you are likely to get from HgS is Vermillion.January 01, 2006

Back

So I decided that it was worth trying to relauch this blog again. It's been over a year since I posted last and much has changed in my life. I certainly don't have more time for this brand of nonsense, so this experiment may be even shorter-lived than the first time around.

But, I reckon, with low expectations from us all it should at least be fun. More on the new name when I have time. Or, take it as a challenge to figure it out. I'll also continue to update the look-and-feel of the site as I have time.